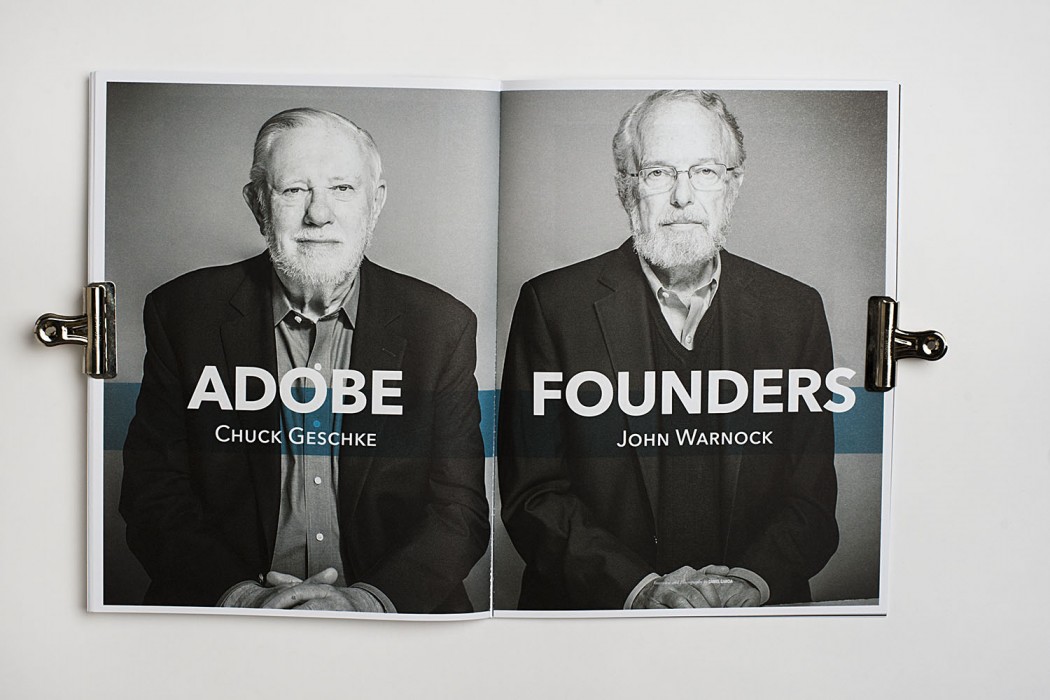

John Warnock and Chuck Geschke met at Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center (Xerox PARC) in the late ’70s but left to form Adobe when they could not convince Xerox executives of the potential market value in developing a printing language that would generate quality fonts and graphics on any printer. The decision to launch their own company has led the revolutionary direction of computer graphics and shaped the publishing and creative communications industries. The influence and effect that these two humble computer engineers and scientists have had is a testimony to their vision, character, and partnership.

Content Magazine: Your first day with Adobe, what was that like?

John Warnock: We didn’t have an office, the first day we started Adobe. We worked out of our houses for a while. We had a computer that we could dial into, and so we started that way.

Chuck Geschke: You know, it’s interesting, there we were, the two of us in this building. You sort of felt like you should shout down the hall, “So, you still there?” Then we began to hire people, so within a couple of months, it at least felt like we were a team of people engaged in working on what was our initial business plan and idea, which of course changed within our very first year in business.

“I’ve always told our employees who want to rise in management, just go out and hire people who are incredibly smart. Smarter than you are, it’s a bigger population from which to choose.”

—Chuck Geschke

What was the original plan?

CG: The original idea that got us our funding was to build a complete turnkey publishing system for marketing inside the Fortune 500, so they could bring a lot of their creative work and their print production in-house.

We were going to build and bring together computers, laser printers, and plate-making equipment, along with all of the software to go into complete production. One of the key ingredients of that was our technology called PostScript, which is a higher level language for describing the appearance of a printed page.

JW: At that time there weren’t PCs broadly available. The workstations at the time were made by Sun Microsystems and Digital Equipment. Those workstations were what people developed software for. The PCs were really very small, just starting to come out, so they weren’t a factor. There were companies like TechSAT and Interleaf that were also building publishing software. There were about five or six competitive companies in the space that we thought we were going into. CG: So shortly after we got into business, one of my professors from Carnegie Mellon who had since left and gone to work for Digital Equipment, Gordon Bell, came by to see what we were doing.

He looked at it, and he said, “Wow that’s interesting. But I don’t need computers, I’m Digital Equipment. And I got a deal with Ricoh in Japan for this laser printer, so I don’t need that, but my problem is they’ve got two or three development teams trying to figure out how to get the computers to talk to the printers in such a way that they can produce the kind of output we want, and they’re not getting anywhere. I see you’re starting to work on the key software that would make that possible. Why don’t you just sell me that software?”

We said, “Well, you know we have this business plan, and it raised two and a half million dollars for us, and we think that’s what we need to do, so we’re going to continue doing it.” He said, “Well if you change your mind, call me.”

JW: About four months in, we got a call from Steve Jobs. Steve had been hiring people away from Xerox PARC, and they were people that we both knew. He said, “I would love to come see you guys and see what you’re doing.”

At that time, that was the beginning of the development of the Mac. First the Lisa was developed, and then the Macintosh. But at that stage he was mostly interested in the Macintosh platform. His problem was, what they could see on the little bitmap screen they could print on a wire-matrix printer—which was horrible. I think he sensed that that was not an ultimate printing solution.

He saw what we were doing, and the people who worked for him knew what we were doing, and so he became very enthusiastic about this software we were developing, which was PostScript.

CG: The first thing he said was, “Why don’t you sell me your company, and come work for me?” We said, “Well, you know, Steve, we really want to build our own business.” He said, “Oh, well, OK, I can understand that. So, how about selling me that software? Because the team I have trying to figure out how to get the computer, the Macintosh, to talk to this laser printer, which I’ve already got a deal for with Canon, aren’t getting anywhere.”

And we said, “Well, you know we have this business plan, Steve. That’s what we think we need to do.” He said, “Well, I think you’re nuts.” So then John and I went to talk to the guy who was chairman of our board, that Bill Hamburg had put in as chairman. We explained to him these conversations we were having. And he said, “Those people are right, you’re nuts. Now you know what your business plan is, go do it.”

When you began Adobe, were you already thinking in terms of adjusting based on market need? Is adapting just part of your personalities?

JW: I think we were flexible. Both of us had a very deep background in technology. What you’re trying to look for is markets and customers. Steve wanted to invest in the company, which he did. The strongest part of our software was the PostScript software. We would have had to develop the rest of the software from scratch, and that was going to take a lot of time and a lot of effort, and since we had ready customers both in Digital Equipment and in Apple, I think that’s what guided us in the direction we went.

CG: You do ask a good question though, “Did we originally think about the fact that we should be building something that was unique and different?” Of course, that’s instinctive to want to do that, but when we got the first check from Bill Hamburg and we were driving home from San Francisco, I asked John, I said, “John, did you ever take a business course?” And he said, “No.” And I said, “Well I haven’t either.”

So we looked at each other and I said, “I think we should stop at Kepler’s and get a book on business.” We did, and there was a chapter in that book called “market gap analysis.”

What it said was, if you want to start a successful business, find a place that isn’t being served, come up with a brand new solution, get it into the market, and by definition you have a hundred percent market share, and shame on you if you can’t keep it. That’s actually pretty much always been our philosophy.

JW: PostScript became a very successful product. It became the standard, and it was saturating the company’s resources, to just keep up with the number of corporations we had to build printer software for. But it was also obvious that you never want to be a one-product company. And so we first started with typefaces for the PostScript printers, but we had worked with drawing programs at Xerox PARC, and thought there was a natural way to map the way that PostScript fundamentally worked with a user interface, and that became Illustrator.

“You don’t have to be ruthless to be a successful business person. You can be understanding, you can be compassionate, you can have all those qualities that make you a good person.”

—John Warnock

You’ve been in partnership for…?

CG: 37 years.

Thirty-seven, which is longer than some marriages.

JW: Probably most.

CG: Except ours.

JW: Chuck and I have a huge amount in common. We have the same number of children, roughly the same ages, roughly the same educational backgrounds in mathematics and in engineering. We both refereed and coached soccer. We’ve been married roughly the same number of years to our wives. We’ve never had an argument, in the 37 years.

Never?

JW: Never.

CG: Never parted company at the end of a work day in anger.

JW: I think our personalities mesh very well. We both have a sense of responsibility to the communities, to the customers, to our stockholders, to our employees. We take very, very seriously the balance that we have for the constituencies of the company.

And I think we both work—with each other and with others—as teams. I don’t think we’re dictatorial in any way. I don’t think we try to micromanage people.

John, how has Chuck balanced out your skill set?

JW: I think we’re great sounding boards for each other, and are both technically very competent. What more do you need? [laughs]

Chuck, what about John? How do you think he has balanced out your skill set?

CG: I think the uniqueness of John is built around his inventiveness, and thinking of things that other people have not thought of before, in terms of what can be done with technology. I’ve always greatly admired that skill.

I think in terms of implementing ideas, we’re very comparable in that regard. I ended up doing a lot more of the negotiating and contract work, particularly in the beginning with PostScript to close deals all over the world that would allow us to make that a universal standard.

John, on the other hand, was the person who really kept focus on what the company needed to do to continue to expand its markets. The thing I found most comforting about our partnership was whenever we needed to do something outside of business—deal with something in our family, or just take a break—we had a hundred percent confidence that the other person would do and make the right decisions. That gave us great freedom. It allowed us to explore and to do things that wouldn’t have been possible if we hadn’t had that confidence in each other.

When you acquired Photoshop, there wasn’t any digital photography [laughs]. You had to see into the future of technology. Even with the cloud, you were one of the first companies to move all your software exclusively to be a download. What led you to innovate?

JW: There was no such thing as illustration programs. There were programs back at Xerox PARC that started to do that kind of thing, but they were never commercially available.

I think, as Chuck said, you’re looking for gaps. You’re looking for problems that have no solution. It was so funny, when we went out on one of our first road trips, the investors said, “Well, how big is the market?” We were puzzled by that, because there was no market. We were in fact creating the technology to create a whole brand new market, and they didn’t understand that and we didn’t understand their question. It was sort of a humorous thing to think about ideas and uses of technology where you’re entering a completely void space.

CG: I think the thing that never concerned us about how big this opportunity was, what we were beginning to understand was, that all visual information was going to transform itself from physical media and distribution to electronic.

If you look at the size of that industry—printing, publishing, entertainment, the whole paper flow business—those are huge. We never felt like we would be constrained by the market opportunity, only by our own ability to invent fast enough to be the first product into that market so that we in fact could have significant market share from the very beginning.

How would you describe yourselves? What are your natural passions?

CG: When I think about myself, first of all, as I already mentioned, no formal training in aspects of business. Throughout my life I’ve been a teacher, I’ve been an engineer, developing things, and I’ve always worked with teams of people.

I think one of my strengths is that I understand what makes a team work. I instinctively believe in people and their ability to do more than they think they can. I really have no fear, never had any fear, of hiring someone who is brighter than I am. I hired him [pointing to John] at Xerox PARC, and I’ve always told our employees who want to rise in management, just go out and hire people who are incredibly smart. Smarter than you are, it’s a bigger population from which to choose. If you do that, eventually there will be nothing for you to do but move up the ladder of the chain of management.

John and I decided early on that we were not going to write elaborate manuals of behavior of what it meant to be an employee at Adobe… The trick is to balance what’s good for each of [your constituencies] in such a way that everyone feels like they’re being well-served. The core principle is you always treat any of those people, including your fellow employees, the way you would want to be treated. And if you do that, you’ll succeed.

JW: In my hobbies, I’m a photographer. I do a lot of drawing and painting, I’m primarily a visual person. It’s funny, it’s a funny balance between mathematics and that visual left-brain / right-brain connection.

The internet today is the perfect communication vehicle, when you want to know something. All my children and grandchildren, they pick up their phones and do the appropriate search, and find out the answer to almost any question you’d want to ask. I think that in some sense amplifies the progress of the society in what you can achieve. In the past, you had to really do research in libraries and go the hard way to find out information. Now information is flowing very freely. And building the tools that allow that to happen, that allow people to communicate in a frictionless way, is what it’s all about.

What would you say, then, is your guiding philosophy?

JW: I think it’s exactly what Chuck said, you treat people the way you would like to be treated. You don’t have to be ruthless to be a successful business person. You can be understanding, you can be compassionate, you can have all those qualities that make you a good person.

CG: I think oftentimes people view two guys who go into business and have the good fortune that we did to be very successful as—they did it for money. But we’re both engineers, and what motivates an engineer is to build something that millions of people will use. We achieved that dream.

JW: It’s not money.

CG: And the money is wonderful, you know, I wouldn’t throw it away. But frankly, I would prefer to take that money and do more things to help other people than use it myself.

What drives your passion, outside of business?

CG: The things that I tend to focus on, are really my family. We’re blessed with seven grandchildren, all the way from second grade to college. Spending time and working with them is part of my passion.

My wife and I have always loved travel, we’ve had a long bucket list of places we wanted to go, many of which we’ve already been to, but we still have some more. We’re going to the Arctic. We’re going to take the whole family on safari next summer. Things of that kind are passions of mine.

[And then the other thing] is to focus on some nonprofits that really make a difference in their community. I just finished a project with a good friend of mine on Nantucket Island, rebuilding the entire Boys & Girls Club, because it’s so critical to the survival of that island. It’s things like that that I spend most of my time on.

Of course, I do think a lot about Adobe, and its business, and where it’s headed, but over time I’ve diversified.

JW: I’ve always been fascinated with the media business. I’m on the board of Sundance. I’m chairman of an online magazine called Salon. I was on the Knight-Ridder board in the newspaper business. I love tracking the media business.

As you see the growth of the internet, and the transitioning out of old media into new media, you see a huge shift in the dynamics of advertising, communication, and how all of that works. Watching the way television and streaming media is changing people’s fundamental behavior, I find fascinating. I’m a student, when I think professionally, of media, and how it works, and how it’s changing. I think the most important thing is how it’s changing, and what the implications are of that to everybody’s life.

Is there anything else you would like to share?

JW: It’s been a hell of a run. [laughs]

CG: We’re the two luckiest guys on Earth.

Full article originally appeared in Issue 8.0 Explore.

Print Version Sold Out