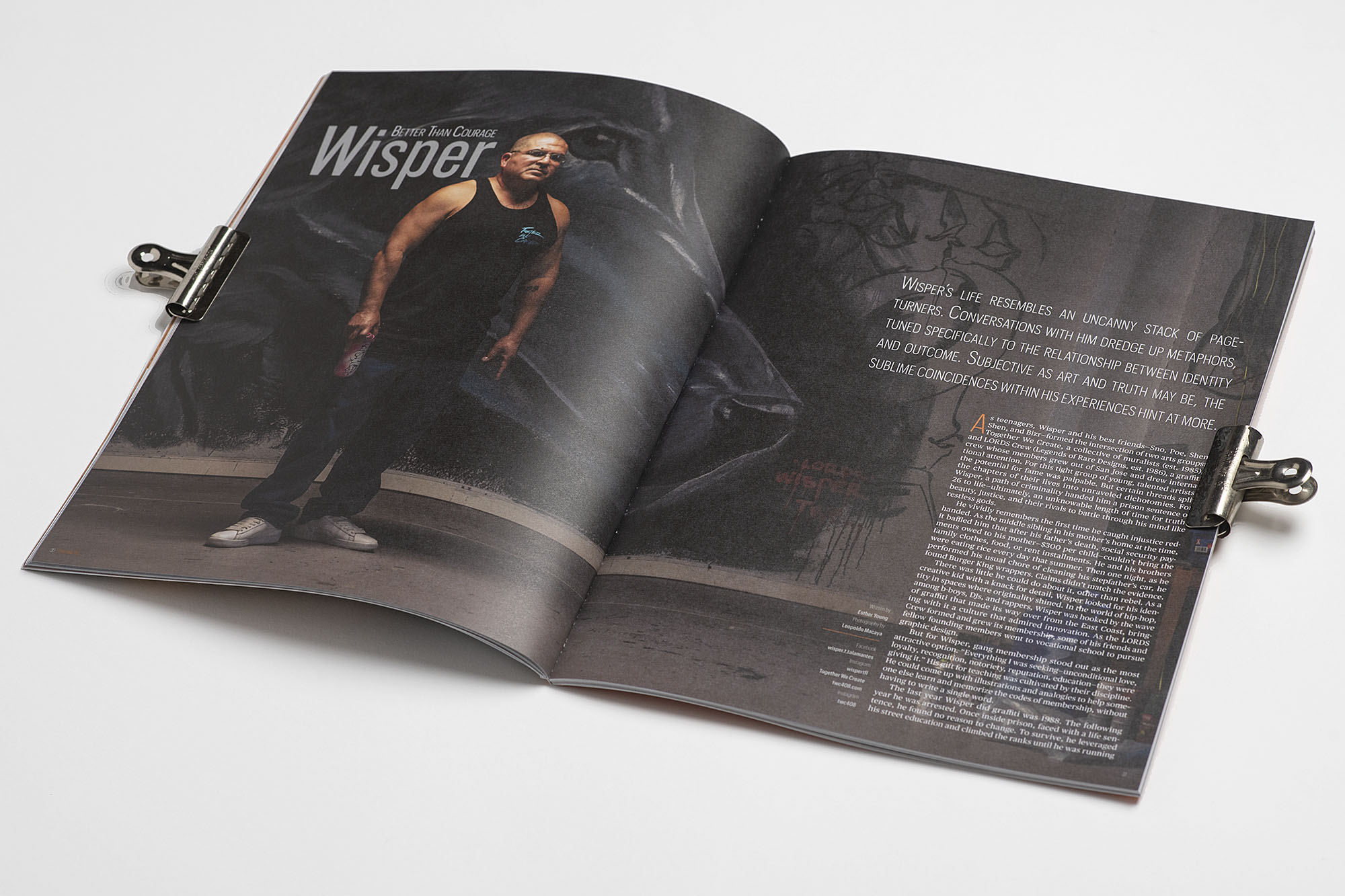

Wisper’s life resembles an uncanny stack of page-turners. Conversations with him dredge up metaphors, tuned specifically to the relationship between identity and outcome. Subjective as art and truth may be, the sublime coincidences within his experiences hint at more.

As teenagers, Wisper and his best friends—Sno, Poe, Shen Shen, and Bizr—formed the intersection of two arts groups: Together We Create, a collective of muralists (est. 1985), and LORDS Crew (Legends of Rare Designs, est. 1986), a graffiti crew whose members grew out of San Jose and drew international attention. For this tight group of young, talented artists, the potential for fame was palpable. But certain threads split the chapters of their lives into unraveled dichotomies. For Wisper, a path of criminality handed him a prison sentence of 26 to life—ultimately, an unknowable length of time for truth, beauty, justice, and their rivals to battle through his mind like

restless gods.

He vividly remembers the first time he caught injustice red-handed. As the middle sibling in his mother’s home at the time, it baffled him that after his father’s death, social security payments owed to his mother—$300 per child—couldn’t bring the family clothes, food, or rent installments. He and his brothers were eating rice every day that summer. Then one night, as he performed his usual chore of cleaning his stepfather’s car, he found Burger King wrappers. Claims didn’t match the evidence.

“If you can learn how to operate from a place of peace while creating art, you can learn how to operate from a place of peace in all aspects of

your life.” _Wisper

There was little he could do about it, other than rebel. As a creative kid with a knack for detail, Wisper looked for his identity in spaces where originality shined. In the world of hip-hop, among b-boys, DJs, and rappers, Wisper was hooked by the wave of graffiti that made its way over from the East Coast, bringing with it a culture that admired innovation. As the LORDS Crew formed and grew its membership, some of his friends and fellow founding members went to vocational school to pursue

graphic design.

But for Wisper, gang membership stood out as the most attractive option. “Everything I was seeking—unconditional love, loyalty, recognition, notoriety, reputation, education—they were giving it.” His gift for teaching was cultivated by their discipline. He could come up with illustrations and analogies to help someone else learn and memorize the codes of membership, without having to write a single word.

The last year Wisper did graffiti was 1988. The following year he was arrested. Once inside prison, faced with a life sentence, he found no reason to change. To survive, he leveraged his street education and climbed the ranks until he was running the yard. The attention and his gang affiliation eventually sent him to solitary confinement in 1994, with other men in solitary confinement “deemed incorrigible.”

In the monotony, Wisper contemplated the value of his life. His path into crime had been a gradual progression of “becoming more and more empty.” As he explains today, “People who commit crimes don’t understand value. If I steal from you, if I vandalize your house…I don’t value you as a person. If my life doesn’t mean something, no one else’s does either.” Even a cup, he reasoned, had worth. It was created for a purpose. Yet like a cup left on the shelf, here he was, a human being locked away in sensory deprivation. If his life had purpose, it couldn’t come from this environment, not from his upbringing, his heritage, or ideologies—which he had been willing to die for. And which he was still affiliated with.

He knew he wanted to change, but change only began when he mustered the courage to revoke his prison gang status, fully aware of the punishment to follow.

Wisper credits supernatural intervention in the events that actually occurred once he lost his status. By the code, he should have died in prison—killed by his own cellmate to protect the rest of the gang. But his life was spared. By the law, he should have been rejected for parole. Involvement with prison gangs was deemed a greater offense than the crime that sentenced him in the first place. But the inmates who would have reported him had been removed from the yard weeks before his arrival.

By the time Wisper came home in 2013, nearly 24 years had passed. His former collaborator, Bizr, had written “FREE WISPER TOUR” on every art piece until Bizr’s passing in 2013, eight months before Wisper’s release. Of the friends who had kept in touch with him, Mesngr was the only one still in San Jose, doing art shows. As he slowly readjusted to life back in society, Wisper decided his goal was to “get my art out, make some money, provide for myself and my family.”

Wisper began looking for opportunities, at times initiating them by reaching out to connections and bringing plywood for the artists to live paint on. As he formed the groundwork to revitalize Together We Create, he also accepted opportunities to speak at high schools and colleges. There were youth who wanted to learn graffiti, and Wisper saw the chance to share about his mistakes so they could make better decisions.

“That’s where I developed a curriculum of teaching peace,” he explains. Acting from a place of courage is revered, but in that state, fear is still present—“you’re acting in spite of fear.” He teaches his mentees to accept responsibility for where they’re at and to apply a faith-based practice until they can believe in themselves. “If you don’t know who you are, you can’t create unique art.”

There are still threads to unravel. To this day, he fights to control the blaze of anger that slices through at injustice. Just like in his youth, he feels the pressure to stay on guard, to secure himself and his safety. “After 24 years of living like that, you don’t just come home and start expressing emotions.” But he knows himself, and he values his life. That deep sense of peace is unshakeable. Hanging around Wisper, friends might not notice how calm and collected he is until he laughs—then, they’re caught by the irreversible, unforgettable belly laugh flying out of him.

This year marks nine years since his release—nine years of using his freedom to help youth secure their self-identity. Often called on to speak and share his story, he is in the final stages of publishing three books that he hopes will aid their discernment. Wisper believes that all people hold a sense of justice, beauty, and truth—but an absence of self-identity spawns a perilous emptiness. “If you’re empty your whole life,” he says, “you don’t know what full is.”

His mission now is to inspire others to create art from a secure sense of identity, free of the pressure to fit a label or hide under a mask. “If you can learn how to operate from a place of peace while creating art,” he promises, “you can learn how to operate from a place of peace in all aspects of your life.”