Askull, a pelvis, some vertebrae—warmly familiar ivory tones and archetypal shapes resonating deep in our memories. Looking closer, the shapes lack the sharp edges of bone. They are fibrous and irresistibly tangible. Stephanie Metz’s studio is filled with such contradictions. Can bone be soft and warm? Can folds of flesh be firm? Everything requires a second look. Each piece provokes.

Bay Area native Metz grew up in Sunnyvale. After studying sculpture at the University of Oregon, she settled back in San Jose with her high tech husband. “When I came back, I didn’t have any connection with anybody art-related around here,” says Metz. With a vague inclination toward animatronics, she put together her portfolio and ended up getting a job with a company in Hayward that did themed environments like the pyramid outside of Fry’s Electronics. She enjoyed the hands-on making part of the job the most, she says. “Just getting back there and doing huge things out of Styrofoam with a chainsaw.” Being told how to produce something was less enjoyable, and the job only lasted a year.

“It’s like alchemy—you take it from one form, and then you do something to it, and it’s another form.”

Metz next tried her hand at working in a frame store. “It was good and it was maddening,” she says. The job brought her into contact with WORKS San Jose, where she did everything from writing grants to becoming president of their all-volunteer board. “It was a good learning experience from the other side in knowing what it’s like to hang a show. I feel as artists we have to work twice as hard to show that we are responsible, thinking business people.”

At the frame shop, she first came across her medium of choice: wool. Someone gave her a Sunset Magazine article about making a little drink cozy out of felt. By simply wrapping a cup in wool and dunking it in hot soapy water, a solid thing could be created. “I was thinking it’s like alchemy—you take it from one form, and then you do something to it, and it’s another form. I went to a local yarn store and was immediately directed to a book on needle felting.”

The process proved fascinating and infinitely variable. By compacting the fibers together with a needle, the resulting felt can be shaped into any form Metz imagines. It can be built up or stripped down, compacted as densely as she desires. “For me, a lot of it is the dichotomy between hard and soft, and sharp and round,” says Metz.

To create the felt, Metz forces the fibers together with really sharp needles notched in one direction. The scales on the fibers interlock and hold tightly together. Although the concept is simple, it affords Metz almost infinite control. Even large forms don’t need much structure because the tightly-bound network of fibers creates its own armature.

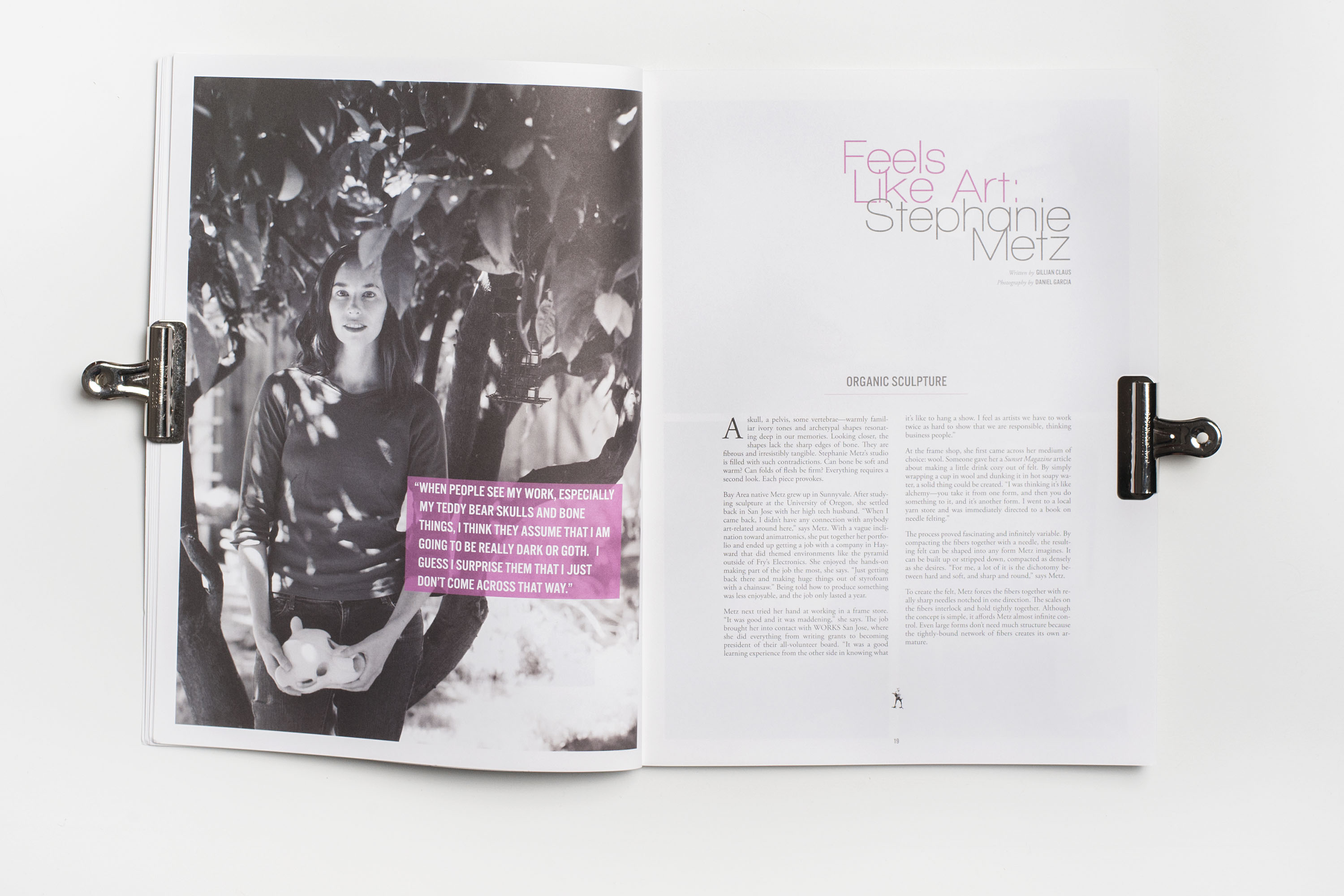

Challenging the way humans have shaped their environment is part of what drives Metz. “It came together in a really nice way to use this organic, really alive-looking stuff to talk about how we shape the world around us.” Her “Teddy Bear Natural History” series explores the anatomy of a found teddy bear with distended snout, oversized eyes and sharp teeth normally hidden behind the fur. Metz explains that the teddy bears evolved out of her experiments with sheep skulls because she was “interested in looking at the hardest part of the animal and making it out of this soft material, but also giving them teeth and thinking about the fact that they’re based on this real creature that could eat any one of us.” The toys mirror the way our culture morphs unpalatable predators into more socially acceptable shapes.

But not everyone feels comfortable with the bears. “Just like with all my work, I find out who’s kind of a kindred spirit and who’s not. Some people see these [skulls] as signs of death, or the death of a childhood icon, and I don’t see them that way at all. For me, they’re specimens of life. Looking at bones talks about what happened in life. It’s not death and gore. It’s the evidence left behind.”

After two years at WORKS, Metz had her first child. Some of her peers made comments about choosing children over art as if the two choices were mutually exclusive. “That probably made me work harder,” says Metz. “I still have things that are galvanizing to me and I feel the need to make something tangible.”

One of Metz’s pieces was featured in the “Milestones: Textiles of Transition” exhibition at the San Jose Museum of Quilts and Textiles (July 21, 2013). From the “Pelts” series, the work featured a baptismal gown fringed with hair. “When I had kids, suddenly I was so in touch with the fact that I am a mammal,” says Metz. “One way we differentiate ourselves from other mammals is we change our hair for aesthetics. Try to grow it in certain places and not in others. I was having the hair come through different clothing pieces as if it were trying to reassert itself—like ivy or moss.”

Having a home studio, Metz’s kids find it “totally normal for mom to be poking wool in the back room.” Her older son loves to draw and already identifies himself as an artist. Her children respect her space and, much as they want to try, she never lets them near the needles. “After ten years of doing it, I still poke myself and it is wickedly painful.”

Her work is becomingly increasingly abstract and large. She is exploring new ways for people to interact with her pieces. “From further away it looks kind of cool and minimalist, clean lines,” says Metz. “But when you get up closer, you see this texture and want to touch it—although you know you’re not supposed to. It makes you think about how physically present it is.”

There is no mystery about her process. Metz has painstakingly documented her work in time-lapse video. “Art is so alienating to people so that’s why I talk about how I do this. I want it to be an entry point, so people can interact with it and feel like art is a part of their lives.”

Metz’s work is certainly physical. It has weight and texture and tugs at something deep in the psyche. Much of it makes me smile. “That’s what I hope to affect in people—that they take a moment in their life and see something differently.”

STEPHANIE METZ

Instagram: stephanie_metz_sculpture

facebook: stephaniemetzsculpture

The article originally appeared in Issue 5.2 “Invent”

Print issue SOLD OUT