A 20,000 square-foot abandoned grocery store on State Street, between Third and Fourth Streets in Los Altos, has recently opened as a modern food hall after four years of planning and repurposing. The project was led by Los Altos Community Investments (LACI) founder and principal Anne Wojcicki, also of 23andMe. She envisioned transforming the space into a vibrant community hub and extension to the Los Altos Farmers Market. LACI partnered with Gensler’s San Jose office to bring that vision to reality.

Two of the primary designers on the project were Brian Corbett and Corinda Wong. They drew from their own life and design experiences to lead the charge to reuse and transform a dormant structure into a welcoming, flowing gathering place with hints of Santa Barbara. With Spanish colonnade elements, the space will be the home of various culinary offerings, including Taiwanese-Korean concept Bo Bèi, local Los Altos favorite Tin Pot Creamery, El Alto by Chef Traci Des Jardins, and even a teaching kitchen. With work done by local craftsmen like Terra Amico, Mission Bell, and hand-painted signs by Ben Henderson, the space is sprinkled with an eclectic mix of tiles to create a venue that Corbett and Wong are not only excited to see opening, but enjoying themselves.

How did you get started in interior design?

Corinda Wong: I started by taking a career test in high school. Architecture, engineering, or accounting came up. My father said, “You would bore yourself to death going into accounting, so choose something else.” So, I just took a shot; I actually didn’t know what interior design was; it was closer to home in terms of college, San Jose State, compared to architecture. So, I went for that.

Brian Corbett: For me, I was always into art as a kid. And, similar to Corinda, I took a test in 11th grade, like career ideas, and it was either an architect, engineer, or psychologist. And I was always into building. So, whenever we had the homecoming parade, I was the one building the floats or leading that team. I was drawn to that. Architecture just always kind of seemed like where I wanted to go with things. And like, instead of going strictly into art, I wanted to kind of take it to the

built environment.

I went to Buffalo University for my undergrad program, which is a great school. Because the economy dropped out in the 60s, this was kind of like an amazing big city that was, you know, not very populated. So much of the projects that we we’re doing, and the thought, was around revitalizing the city. I really developed a passion for cities at that point in time. Eventually, when I went to grad school at Columbia in New York, I worked for a few internships, doing high-end residential apartments and then got a job with a professor doing schools and community centers, which turned out to be a really great experience, and so much of it I found in New York, even though it’s architecture firms, they do a lot of interiors. And that was something I really hadn’t considered before.

But eventually, I married my wife, who I met in grad school. She’s from San Jose. And she wanted to move out here after we lived in New York for a few years. So we made the trek, and I began looking around for jobs. I found Gensler, a small office right downtown. I went in and interviewed; they were 15 people at the time. And that office, I guess, was really an outpost from when they were working on the airport. But they did mostly interiors. I kind of pivoted my career at that point in time. And over time, I really fell in love with it and making an impact on the spaces that people are in.

Corinda, how did you get to Gensler?

CW: For years, I worked in San Francisco for one design guy—for maybe eight or nine years. I was then part of that whole slump in terms of work slimmed down in the economy. So, I actually took some time off and explored floristry for a while.

I had a friend who had a friend who worked for Gensler in accounting. I wasn’t actually looking for a job, and she said, “Hey, just give me your resume.” I said, “Okay, here it is.” I got a call maybe eight months later, very randomly, from Kevin Schaefer in San Jose, and he said, “Hey, why don’t you come on in and let’s talk.” We talked for maybe two hours with him and the design director at the time, John Scouffas. And I wanted to come work for them. They were sort of this source of just a familial sense of what design could be. And it brought me back to San Jose, where I started my schooling, and it was great.

Gensler has several tech company clients, which means those projects are not visible to the public; what’s some of the places that you’ve worked on that are public?

BC: I think the first one we did was HanaHaus (456 University Ave, Palo Alto). That was actually similar to the State Street Market project in some respects. It was the old Varsity Theatre that later became a Borders bookstore and then sat abandoned for many years…That kind of partnership with working space, high-end retail, and coffee really draws people together. So, reactivating that courtyard felt really good as well. And every time we go by there, that place is packed. MiniBoss (52 E Santa Clara St, San Jose) is another one of those enjoyable projects, and those guys are great.

CW: I’d say Moment in the parking garage by San Pedro Square Market. We were part of the original planning way back years ago. Some projects take a long time to come to fruition. But it’s great when you see people interact. It’s great to see the excitement when you bring life back to a corner, or especially to spaces that have been abandoned. HanaHaus was an empty theater, the corner where MiniBoss is was dormant—so that is

very rewarding.

What are some of the unique aspects of the State Street Market?

BC: I think a plus is that we’re able to reuse the existing building. Though that’s probably a plus and minus. We can get into that. But, definitely a plus from a sustainability point of view. It might have been cheaper to knock this thing down and rebuild it, but it would be a whole lot less sustainable. We save a ton of carbon by repurposing it.

And, keeping that authentic feel in Los Altos, I think there would have been a lot of hesitation to have something new and modern, or potentially larger here—so, keeping that same authentic vibe, but bringing it back to life in a different way.

CW: There has been a lot of sort of sensitivity on that. I think the location was the first thing. Usually, in architecture and design, when it’s brand new, you’re picking the right spot; this location was already here. They had a vision that it would be an extension to the Farmers Market. And that created those first design triggers of what the storefront and facade could be, how that can invite people in. I think that was the initial sort of pluses. It had the bones, though it had a couple of decades of modification. To lose the story within it would be just a travesty.

BC: The building itself is pretty interesting. It was like a one-story grocery store, like mid-century modern, kind of built in the 50s. And it was covered up, later adding a second story and turned into this kind of mission-style building.

What was nice about it, like when Corinda talked about its bones, there’s a central dome that used to be there that gives you that big grocery feeling. When that was opened up, it just lent itself to this community space. I think that was something that definitely worked out well for the project.

At what point were you brought into the project? Did the developer come to you and say, “Hey, I have this building, what can we

do with it?”

BC: They wanted to do a food hall and probably offices upstairs. So they came in with a pretty good vision around that in terms of, like, operation model and specific program that wasn’t really figured out. But they came to us with that. And then we worked with them for a few months, really developing concepts and, like Corinda said, Anne’s vision (Anne Wojcicki, cofounder of 23andMe and principal and founder of LACI) is that of a local Los Altos resident, and she loves that Farmers Market there. And she really wanted to create a permanent extension of the Farmers Market and have that same vibe. So, a lot of the concepts revolved around that.

CW: Well, it’s also a multigenerational community, kind of a little township here. So it was really to create a space that would fit three generations—from your newborn babies, your grandmothers, to your after work hangout happy hour, a place that everybody can come to, whether after baseball games or bike rides. I remember Anne was saying that everybody can actually go and have food together. And that was a missing piece to Los Altos.

What you’re talking about is “place making.” Is that concept taught in your training? How did that idea come into the State Street Market?

BC: It’s definitely part of my education, at least within architecture. And what I was doing in Buffalo, so much of the work was trying to make “place” there.

In this project, it was definitely a focus. Robert Hindman (Managing Director, LACI) is very into place making as well. And we had shared values on how this project could come to fruition in that sense.

CW: In my education, that wasn’t part of it. I was in interior design, so it wasn’t about that exterior; it was more inbound. So a lot of this, I think, came from just being in school in San Jose State, watching that city kind of stand still for a long time, and being part of Gensler for 14 to 15 years and watching the city actually start to come alive and the impact that we can have slowly. It took a long time to make minimal steps, but you could see the significant impact that can be made. And we at Gensler were in some kind of forward vantage point; I think that’s the momentum that I’ve gotten from place making. I saw it sort of working from the middle of it and from watching it and being a part of it.

BC: Even before we were awarded the project or competing on it, we developed some sketches and ideas of what might happen. A lot of it is actually what we ended up doing. But it was all about place making. In the end, it was all about slight modifications to the building that created activity. And so, like the idea of widening the breezeway and making that an outdoor dining area or extending the arcade and making that outdoor space, we kind of painted a picture really early on.

But we had these solid ideas all around place making, more so than the design initially. Then, of course, the

design followed.

With State Street Market recently opening, what are you proud of?

BC: I think some of the ideas that we brought to the table will have a significant impact; we feel very proud of the modifications to the Paseo into the arcade to create that outdoor space. We think it’s going to be really active and create a great street presence.

The widening the pass-through—that connectivity is going to be a big deal. We had a soft opening, and that space was super-well utilized, and it felt really good, felt activated. And then the front arcade, people walking by on the sidewalk, are naturally drawn in there. And they want to be part of it. So those are the two big moves for me.

But also, that central space and opening up that dome—it was all closed in the previous iteration, but it just created this amazing space once it was opened up. So, I think I’m very proud of creating that gathering space, both on the interior and the exterior.

CW: My background is interiors, but I had a hand in this project’s exterior architectural design, and that part is quite fun for me. And the best aspect of that is when you hear from the community, or Robert Hindman tells us that people will walk by and say, “Wasn’t the building always like this?” That fitting into the context and fabric of the community—I think it is the best thing when people peer in and they’re excited to see it. That’s exciting to have this space be part of their world. I think that’s amazing.

Also, the secondary tier—I love the idea of design cues that give people this notion of “Oh, something to do.” So, adding simple things like awnings to the corner, where it signifies, “Hey, it’s retail. Come on in.” Then for the storefronts themselves, the windows, they were short. We elongated them from the top of the ceiling to the floor. That’s again, open it up with a “Come on in” visual cue.

Where do you find inspiration for designing a building like State Street?

BC: A lot of it is experiences, I think—like going and visiting as many places as you can, whether it’s overseas or even locally, and gathering those experiences and keeping an eye out as you’re there for what you like, what feels right, and trying to have a deep memory of those experiences, so you can draw back on those.

CW: I always used to tell people that it’s great when you experience things, and it becomes slightly fuzzy because then you would not ever mimic something. But you would create from that feeling in yourself—like what you remember of it. So, it’s great to be slightly forgetful.

And, we are from a different generation; as much as I love them, we approach inspiration differently than looking at Pinterest and collecting images. Now there is a lot of design starts that way. But when you’re a little older, you’ve gone to a few more places, you can rely on other things—create your own “Rolodex.” And, usually those things are not merely visual; they’re inspired from experiences or literature, even songs. It’s paintings and a picture, or a feeling that you might want to bring into what you are creating.

What are some of the design elements that are here that make this place unique?

BC: The tile. There are 40 different tiles in this space. And that was something that Anne really wanted. It is almost something to be discovered throughout the space. Not that we selected all of it. We had a hand in a lot of it, but so many people had their hands in selecting the tile. So that’s kind of a cool feature. With each of the risers on the stairs to the second floor throughout the exterior, you’ll see that each tile is different.

CW: Yeah, I mean, and [Anne] wanted actually to reuse a lot of tiles that she didn’t use on another project. So, that was also a bit of a sustainability part of this project. I was like, “What are you gonna do? You have one box of this, one box of that. It’s not enough to do all.” But we patched it together, and it’s a great story because of that point, right? Not wasting very much.

They’re hidden in some of the private spaces. So every bathroom is a little different. So if you go on a bathroom hunt, you’ll see that they are different. Maybe that’s a “game” that people can do. There is a lot of tiles.

BC: Yeah, I think the other thing is the arched windows. I think they are really cool. They really brought this building, I think, closer to what they want it to be.

And from a furniture perspective, we paired our client here, Los Altos Community Investment, with Terra Amico. And they brought a lot of unique elements. They built tables from reclaimed bowling alley wood, and made it a feature, with a lot of reclaimed wood, to make interesting installations throughout the space.

CW: Also, the signage was painted by Ben Henderson, who worked with us at Gensler for a while. We introduced him to the client about two years ago. And Robert Hindman brought him in to do a lot of hand painting of the signs.

BC: I love the work that Ben does. And we definitely had a vision of his style of hand-painting, hand-lettering, how that would fit really well here. And we’re so glad that they hired him because he’s been adding a lot of cool features throughout.

For someone looking for some design principles, for example, if someone is redoing their kitchen, what are some design guidelines?

CW: It should be functional first. Right? I always say that. As for your height of countertops in your home, if you’re super tall, you can actually adjust that. In commercial, you don’t have that luxury. There’s a standard. There are laws. But I think you can always think of where you want your focus to be. What is the first thing you want your eye to go toward, right? Is it the hood? Is it the backsplash? Is it important that the island is central, where everybody gathers? I think making those first initial choices can define what your other selections are.

BC: I was going to say storage, so you can keep it minimal.

CW: Hide everything. [Laughter.]

BC: Exactly. Keep it clean.

What advice would you give to somebody looking to get into a career in architecture or interior design?

BC: We’re hiring. [Laughter.] I think that with automation coming our way, that’s always something I’m worried about with the profession’s future. We’re employing it more but more as a tool for designers. But, ultimately, I think we’re the profession that is going to go more toward the creative outlet and the relationship-building with the clients; that is where the profession is ultimately going to have to go. It’s going to be the design creativity and in that client relationship. I think a lot of the technical aspects and the drafting will become very automated over time. You can have a 10-story-tall building, and it will populate the whole thing for you. And you can change the layouts, and it gives you all the counts automatically. But that’s not design, right?

CW: That’s algorithms. It’s like a quick first pass. It’s iterations, but it’s not design. The missing thing is going back to human experience like that “Rolodex” I was talking about, the experiences you’re trying to create. I don’t think computers will ever be able to do that. And I think that’s what anyone interested in this profession really needs to be thinking about. It’s always going to be about the human experience instead of the more technical aspects in terms of drafting and drawing and computer modeling and things like that.

I’m on the oozy-gooey side because it is about your passion. You want to come in and do something creative. We’re part of a small percentage of fields where things get built; there’s an actual object, a thing, from your brain that comes out. But you actually have to love it, because it is hard work. Your brain is constantly working, and you’re training it all the time. And innovation needs to happen. Creativity has to happen, and that’s not usually on that time schedule. Not normally. But the rewards are what you can create and see. That one moment when you get your first project, and it gets built, and you hear somebody say, “Ah.” That is amazing.

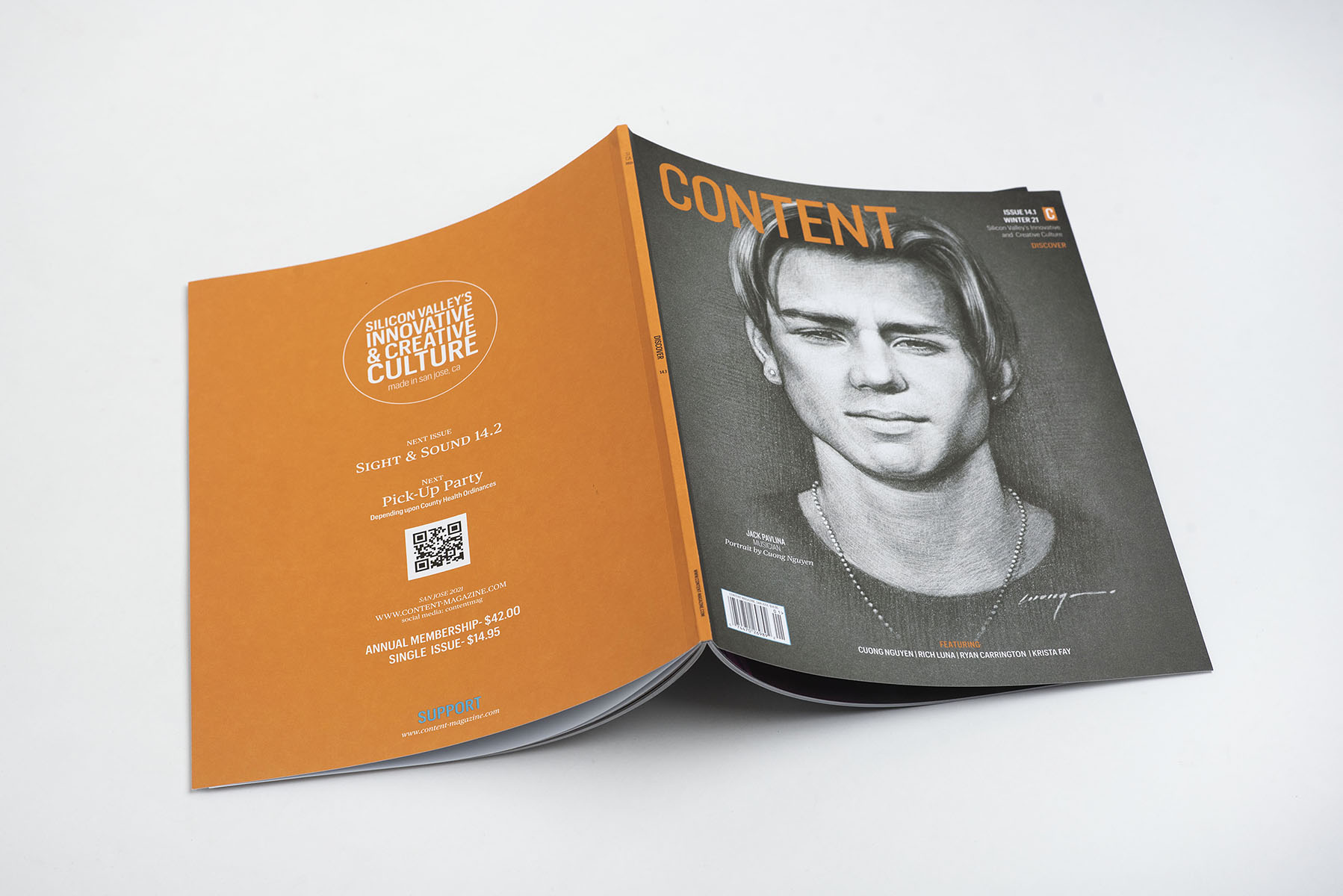

Article originally appeared in Issue 14.1 Discover (Print SOLD OUT)