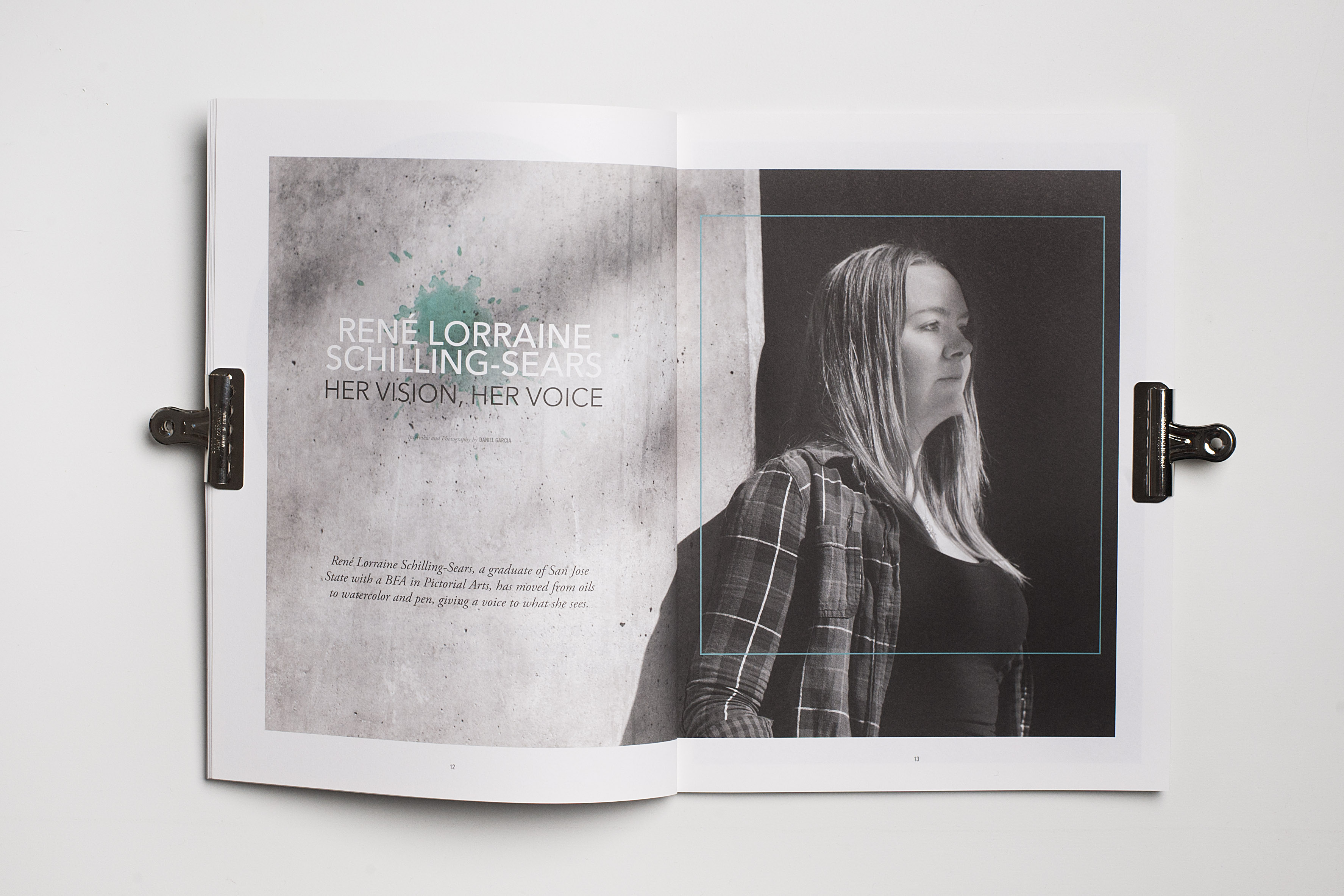

René Lorraine Schilling-Sears, a graduate of San Jose State with a BFA in Pictorial Arts, has moved from oils to watercolor and pen, giving a voice to what she sees.

Was there a time when you had that “aha moment,” when you released your voice?

Yeah, absolutely. I had an instructor when I was at San Jose State who really got through to me. It was one of those things where you’re working on a painting and you finally see something that you hadn’t felt for decades. It finally just happened on the canvas.

Do you remember what that painting was?

Yes, I still have it too. I was working on my BFA show. My whole series was about body art, tattoos, piercings, things like that. That’s what I had been working on for the last two years at that point. It was a single fingernail. I was working on painting a hand. It was a single fingernail, and it was like, “Oh, this is what I want to do forever.”

When you look back at that piece, what’s your feeling about it?

I am in love with that piece so much that I feel like I’ll never be able to top it for myself. I’ve been offered a lot of money for it. There’s no way. It feels like my firstborn child, because I had such a connecting moment to it. It’s going to stay with me forever.

What was that about? Was it the type of technique that you used?

That’s hard. That’s a hard thing to put into words. At that moment, I felt I finally believed in myself with the title of “artist.” I was satisfied with the work that I’d done to the point where I felt like I could finally own the title artist, because that is always a struggle.

When you grow up in the Bay Area with a lot of amazing artists, you see so many paintings and artworks and people really making it happen. You think, “How am I ever going to compete with them?”

You have three different styles in your portfolio: oil, pencil, and watercolor. Which is your favorite?

I prefer watercolor and ink, which is crazy, because when I started painting, I never thought that I would do watercolor or watercolor portraits. It was the furthest thing that I thought I would ever be interested in. I was always just an oil lover and a canvas lover, but I think there’s something very intimate about sitting down with watercolor and ink, something that seems more personal. I like that. Oil is fun, too, but at this point to me…I’m just not personally as connected to it anymore.

Your watercolor ink portraits have a very unique aspect, with the subjects’ faces missing. I hear it is because of a degenerative eye disorder, is that right?

I have neurological issues. I have a cyst in my brain that causes balance issues and visual disturbances. The left side of my temporal lobe fires at half the rate that the right side does. There’s some disconnect there. Also, I have holes in my vision.

Some days, it’s like I’m looking through a wheel of Swiss cheese. It started in 2011. The doctors still are not really sure what it is. The holes in my vision, they’re not really sure where it stems from. They think it’s related to the other things that are happening. It’s really difficult to explain to people and hard to convey what I am going through, so I really wanted to put that on paper.

Why are you choosing this particular medium—pen and watercolor—for these portraits?

One of the reasons I do pen and watercolor in the same piece is because I feel a lot of times when I can’t see very well, it’s hard to feel grounded. I use the watercolor to show and convey that whole feeling that things are happening. When you work with watercolor, things will just happen that you can’t pick up off that paper. You can’t wipe it off. That’s how I feel with these spots in my eyes. They’re not going away. I can’t wipe them away. The hard lines that I use, that are more pencil or Micron pen, are my way of conveying those moments that are calm, that say “Everything is in place.” That’s how I’m trying to meld both of those together.

How does it feel then, when people are attracted to your work and find out your story? Is there a little bit of insecurity or concern? Are you wanting to share it?

Personally, I feel that things are less scary when you talk about them. On the one hand, I wouldn’t put the story out there, but on the other, when I did the show here, I titled it with the condition that I have. It gave me the chance to talk to 30 people—strangers—about it.

Putting it out there is easier because when I talk about things, I feel like they’re less scary. They don’t seem as crazy. At the same time, I don’t want my work to be all about my condition. I don’t want people to only pay attention to it because the story has a really personal health issue involved.

I imagine you don’t want your health issue to be the reason people notice your work, but it is part of your story. I was very attracted to your work, knowing that you had neurological issues.

It’s hard. It’s a hard balance. I think, for the most part, people…like you just said, you liked it before you knew the story. I hope that continues, but at the same time, it’s also really cool. I’ve met some cool people who have similar conditions. They can see that within the art. They can relate to it.

You’ve had this current series. What are you working on now? What’s next for you?

I’m still expanding this series, but I want to bring more medical devices and machinery into it. I have a show coming up in the fall in San Francisco, so I’ve got about eight months or so to finish this body of work, or at least a couple new pieces. That’s what I really want to do. I want to bring the medical equipment side to it, just to evoke more of those feelings, and get more people to be able to connect with the pieces. A lot of times a portrait is a portrait, and you need something else in there to show or help along the thought process. I think the juxtaposition might be just right.

What’s the greatest lesson you’ve learned in life through your painting?

What I always come back to is a moment in college, where a professor told me to eliminate something from a painting, and I did it without even thinking. I hated that painting from that moment on. I could never get that piece back to what I wanted it to look like.

I always go back to that moment, in all sorts of experiences, and remember to always stop and think and not take somebody else’s opinion without really figuring out if it’s right for you. It’s interesting that I learned that through painting.

See more of René’s work on here wbesite renelorraine.com

And, on here Instagram @renelorraine

This article originally appeared in Issue 10.4 “Profiles”