We’ve seen the lockdown footage of folks in urban areas dancing on apartment balconies—a hopeful sign of life and defiance during COVID.

Yet, how does a professional dancer survive a global pandemic?

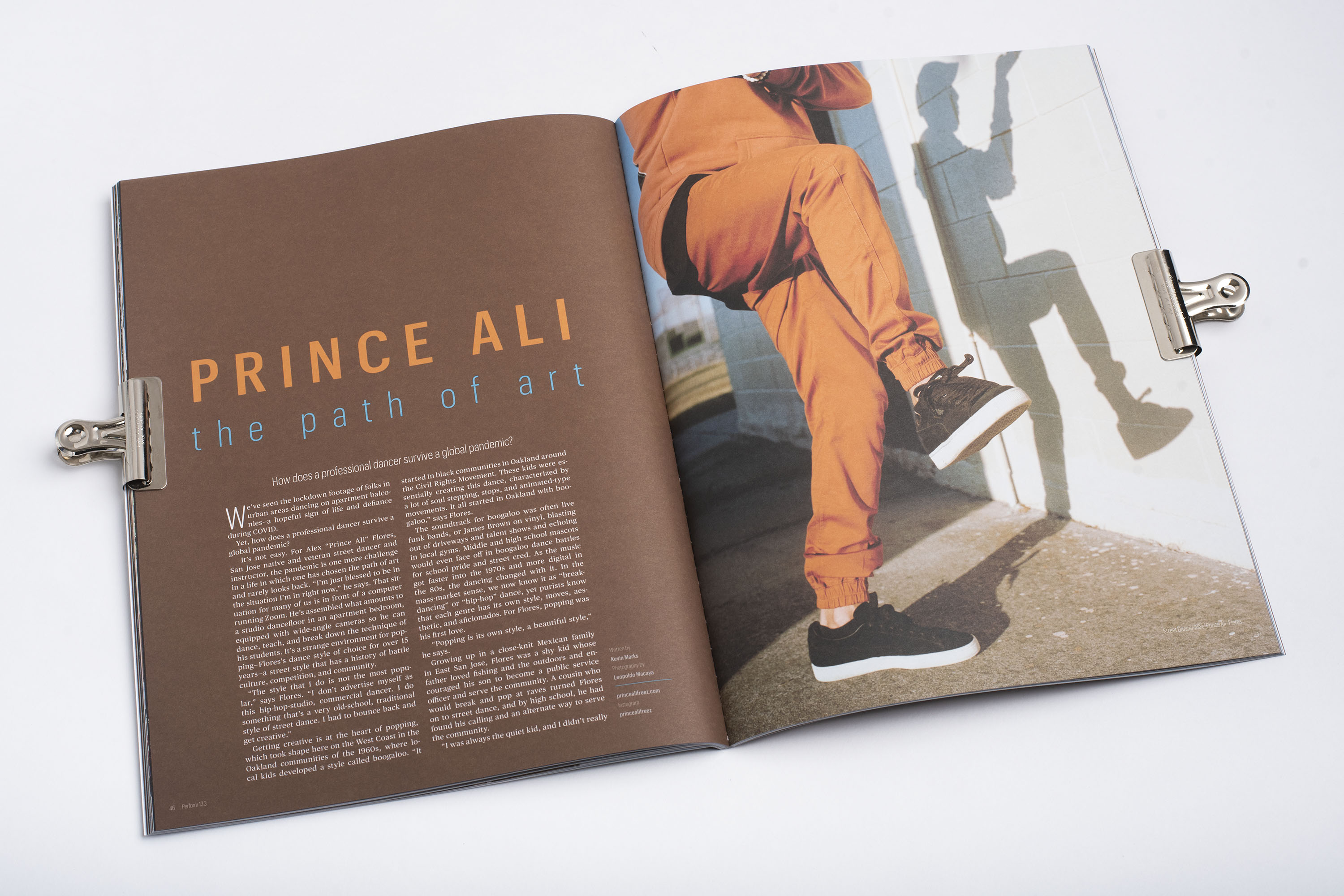

It’s not easy. For Alex “Prince Ali” Flores, San Jose native and veteran street dancer and instructor, the pandemic is one more challenge in a life in which one has chosen the path of art and rarely looks back. “I’m just blessed to be in the situation I’m in right now,” he says. That situation for many of us is in front of a computer running Zoom. He’s assembled what amounts to a studio dancefloor in an apartment bedroom, equipped with wide-angle cameras so he can dance, teach, and break down the technique of his students. It’s a strange environment for popping—Flores’s dance style of choice for over 15 years—a street style that has a history of battle culture, competition, and community.

“The style that I do is not the most popular,” says Flores. “I don’t advertise myself as this hip-hop-studio, commercial dancer. I do something that’s a very old-school, traditional style of street dance. I had to bounce back and

get creative.”

Getting creative is at the heart of popping, which took shape here on the West Coast in the Oakland communities of the 1960s, where local kids developed a style called boogaloo. “It started in black communities in Oakland around the Civil Rights Movement. These kids were essentially creating this dance, characterized by a lot of soul stepping, stops, and animated-type movements. It all started in Oakland with boogaloo,” says Flores.

The soundtrack for boogaloo was often live funk bands, or James Brown on vinyl, blasting out of driveways and talent shows and echoing in local gyms. Middle and high school mascots would even face off in boogaloo dance battles for school pride and street cred. As the music got faster into the 1970s and more digital in the 80s, the dancing changed with it. In the mass-market sense, we now know it as “breakdancing” or “hip-hop” dance, yet purists know that each genre has its own style, moves, aesthetic, and aficionados. For Flores, popping was his first love.

“Popping is its own style, a beautiful style,” he says.

Growing up in a close-knit Mexican family in East San Jose, Flores was a shy kid whose father loved fishing and the outdoors and encouraged his son to become a public service officer and serve the community. A cousin who would break and pop at raves turned Flores on to street dance, and by high school, he had found his calling and an alternate way to serve the community.

“I was always the quiet kid, and I didn’t really have a voice in school,” says Flores. “I was always the wallflower in the back. I made this conscious choice. I’m going to do this. This is the thing I’m going to focus my energy on.”

Popping provided a focus, a passion, and a way to navigate adolescence and avoid gang culture in the neighborhood. He befriended local dancers Aiko Shirakawa and San Jose legend Spacewalker, who mentored him and critiqued his moves. It was urban folk art happening in the moment.

“There really was no school for popping. The way we learned was by being around people. It was very organic,” says Flores.

As he grew older, he continued to learn from the most established Bay Area dance crews, such as Playboyz Inc and Renegade Rockers, until a hallelujah moment arrived with an offer from Bobby and Damone from Future Arts, who offered him a salary equal to his day job to teach dance. He jumped at the chance.

He continued to work on his craft, teach, and compete until winning his first world title for popping in 2019 at the Freestyle Session World Finals in San Diego, a seminal moment for his career and his art.

The arts in general, and street dance in particular, are in a curious position in 2021. Superstar-sponsored, mass-market dance shows are reintroducing wide swaths of the population to dance and choreography, yet perhaps missing the point when it comes to freestyle and street dance, which is more immediate and of-the-moment, like jazz and hip-hop. For Flores, who has served as a judge and showcase artist for shows like World of Dance, he sees the world turning on to dance, but also tries to stay true to the form, even as street dance in general evolves and emerges.

While acknowledging that the competitive aspect of popping and street dance will always be a part of the form, Flores imagines a focus for street dance in the post-pandemic landscape that leans more toward helping one another through art, instead of trying to prove who’s best. He sees the city of San Jose and its communities as part of that equation.

“If we can have some sort of facility where artists can go and get paid their worth, that would be amazing,” says Flores.

Among his many dance education offerings, Flores teaches an intensive dance boot camp called “The Renegade Way,” which seems to describe the ethos one must have to pursue a life in street dance. For Alex Flores, his smile is disarming and his demeanor is warm and friendly, but when it comes to dance, his determination is evident.

“I’ll never stop dancing,” he says.

Instagram: princealifreez

Article originally appeared inIssue 13.3 Perform (Print SOLD OUT)