O n Solace, Inclusion, and Poetry as Story

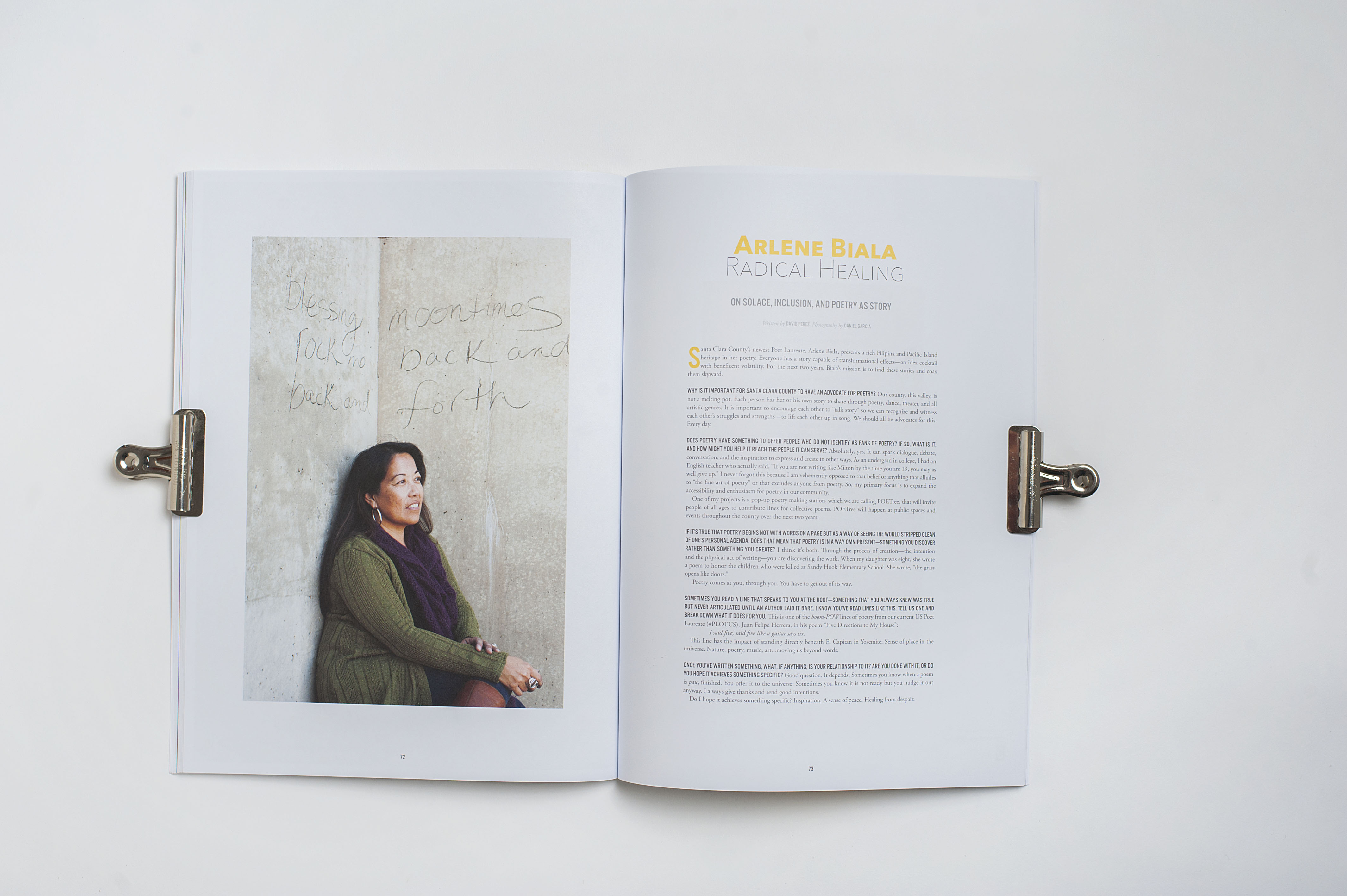

Santa Clara County’s newest Poet Laureate, Arlene Biala, presents a rich Filipina and Pacific Islander heritage in her poetry. Everyone has a story capable of transformational effects—an idea cocktail with beneficent volatility. For the next two years, Biala’s mission is to find these stories and coax them skyward.

Why is it important for Santa Clara County to have an advocate for poetry?

Our county, this valley, is not a melting pot. Each person has her or his own story to share through poetry, dance, theater, and all artistic genres. It is important to encourage each other to “talk story” so we can recognize and witness each other’s struggles and strengths—to lift each other up in song. We should all be advocates for this. Every day.

Does poetry have something to offer people who do not identify as fans of poetry? If so, what is it, and how might you help it reach the people it can serve?

Absolutely, yes. It can spark dialogue, debate, conversation, and the inspiration to express and create in other ways. As an undergrad in college, I had an English teacher who actually said, “If you are not writing like Milton by the time you are 19, you may as well give up.” I never forgot this because I am vehemently opposed to that belief or anything that alludes to “the fine art of poetry” or that excludes anyone from poetry. So, my primary focus is to expand the accessibility and enthusiasm for poetry in our community.

One of my projects is a pop-up poetry-making station, which we are calling POETree, that will invite people of all ages to contribute lines for collective poems. POETree will happen at public spaces and events throughout the county over the next two years.

If it’s true that poetry begins not with words on a page but as a way of seeing the world stripped clean of one’s personal agenda, does that mean that poetry is in a way omnipresent—something you discover rather than something you create?

I think it’s both. Through the process of creation—the intention and the physical act of writing—you are discovering the work. When my daughter was eight, she wrote a poem to honor the children who were killed at Sandy Hook Elementary School. She wrote, “The grass opens like doors.”

Poetry comes at you, through you. You have to get out of its way.

Sometimes you read a line that speaks to you at the root—something that you always knew was true, but never articulated until an author laid it bare. I know you’ve read lines like this. Tell us one, and break down what it does for you.

This is one of the boom-POW lines of poetry from our current US Poet Laureate (#PLOTUS), Juan Felipe Herrera, in his poem “Five Directions to My House”:

I said five, said five like a guitar says six.

This line has the impact of standing directly beneath El Capitan in Yosemite. Sense of place in the universe. Nature, poetry, music, art…moving us beyond words.

Once you’ve written something, what, if anything, is your relationship to it? Are you done with it, or do you hope it achieves something specific?

Good question. It depends. Sometimes you know when a poem is pau, finished. You offer it to the universe. Sometimes you know it is not ready, but you nudge it out anyway. I always give thanks and send good intentions.

Do I hope it achieves something specific? Inspiration. A sense of peace. Healing from despair.

ARLENE BIALA

instagram: bialabong

This article originally appeared in Issue 8.1 “Sight and Sound”.