Two robotic arms swivel in long arcs over a gallery wall. A sizeable crowd of art goers watch the appendages dance in long, sweeping rotations that give way to finer, more delicate gestures. At the end of each arm is a small pointer, kind of like a pinball flipper. As with any other art piece, people observe for a few beats then move on. But there’s one moment no one walks away from—a part of the dance that has everyone hooked. At one point, the arms move painfully slow, and the two little flippers move to touch. The closer they get, the slower they go. And here’s the thing…No one can breathe. Everyone is stone silent, dying for these two flippers to make contact.

Why?

These are two slabs of aluminum and steel powered by motors pulling on rubber cabling. How then is it so irrefutably human? Why is it able to tell a story about connection and disconnection that is so familiar? Artist Alan Rath has provoked these questions for the past four decades, and they’re as relevant now as they have ever been.

Of the connection between people and machines, Rath observes, “There’s something about building machines that makes you think about nature and ourselves. Most machinery is modeled on nature, modeled on the body, and now starting to be modeled on the mind. That’s why I don’t think it’s so alien. It’s really just us being projected.”

The piece with the robot arms and little flippers, entitled Again, beautifully illustrates this point about projection. It’s thoroughly mechanical. The metal isn’t disguised to seem more human, and still it reminds us of ourselves. As such, this robotic movement has the power to recall ancient human dramas about desire and loss. Yes, we’re staring at technology, but we can’t help but lay our own stories over it. Is this the reason the arms look vaguely skeletal in the first place?

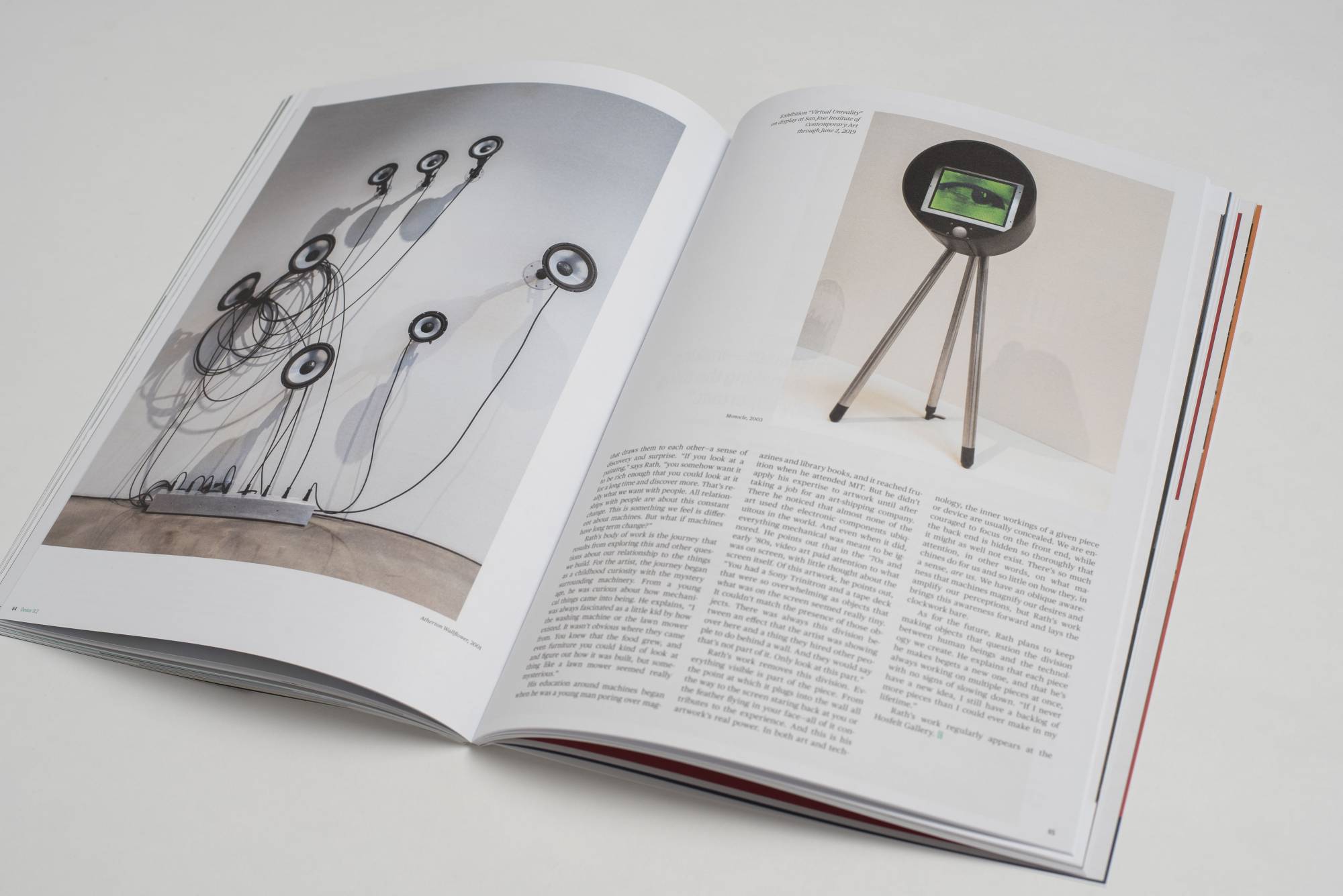

So much of Rath’s work evokes this kind of self-reflection, sometimes with displays of animated eyes, hands, and mouths or with pieces like Vanity, where a human face on a screen looks into a mirror. But the same effect—of a machine evoking lifelike qualities—shows up in different ways. In another part of the gallery, an aluminum pole extends from floor to ceiling. At its top end, pheasant feathers radiate outward like flower petals. Motors cause the plumage to flutter, as if the piece is preparing to take flight.

Whether it’s an image on screen or feathers overhead, a crucial tool makes the pieces work together as a cohesive whole. Algorithms. Algorithms govern all the motion. “They’re not recordings,” Rath explains. “I want to make machines that are playful and funny—that people respond to as living things. The algorithms just keep on unfolding. They don’t have a predictable loop.”

Rath’s work constantly challenges convenient divisions between the natural and the synthetic, and not always in ways that are immediately apparent at a gallery show. Some pieces alter their behavior years or even decades after they’re created. Examples of this can be found in his Running Man pieces. According to Rath, “Sometimes he’ll be running to the left, sometimes to the right. Some days he’s kind of confused, running back and forth, changing color and speed on a daily basis, but then there are these much longer things that happened over years.” As for what changes these are, it’s up to whoever takes them home to find out.

This spontaneous quality suggests that what draws people to art is the same thing that draws them to each other—a sense of discovery and surprise. “If you look at a painting,” says Rath, “you somehow want it to be rich enough that you could look at it for a long time and discover more. That’s really what we want with people. All relationships with people are about this constant change. This is something we feel is different about machines. But what if machines have long term change?”

Rath’s body of work is the journey that results from exploring this and other questions about our relationship to the things we build. For the artist, the journey began as a childhood curiosity with the mystery surrounding machinery. From a young age, he was curious about how mechanical things came into being. He explains, “I was always fascinated as a little kid by how the washing machine or the lawn mower existed. It wasn’t obvious where they came from. You knew that the food grew, and even furniture you could kind of look at and figure out how it was built, but something like a lawn mower seemed really mysterious.”

His education around machines began when he was a young man poring over magazines and library books, and it reached fruition when he attended MIT. But he didn’t apply his expertise to artwork until after taking a job for an art-shipping company. There he noticed that almost none of the art used the electronic components ubiquitous in the world. And even when it did, everything mechanical was meant to be ignored. He points out that in the ’70s and early ’80s, video art paid attention to what was on screen, with little thought about the screen itself. Of this artwork, he points out, “You had a Sony Trinitron and a tape deck that were so overwhelming as objects that what was on the screen seemed really tiny. It couldn’t match the presence of those objects. There was always this division between an effect that the artist was showing over here and a thing they hired other people to do behind a wall. And they would say that’s not part of it. Only look at this part.

“There’s something about building machines that makes you think about nature and ourselves. Most machinery is modeled on nature, modeled on the body, and now starting to be modeled on the mind. That’s why I don’t think it’s so alien. It’s really just us being projected.”

Rath’s work removes this division. Everything visible is part of the piece. From the point at which it plugs into the wall all the way to the screen staring back at you or the feather flying in your face—all of it contributes to the experience. And this is his artwork’s real power. In both art and technology, the inner workings of a given piece or device are usually concealed. We are encouraged to focus on the front end, while the back end is hidden so thoroughly that it might as well not exist. There’s so much attention, in other words, on what machines do for us and so little on how they, in a sense, are us. We have an oblique awareness that machines magnify our desires and amplify our perceptions, but Rath’s work brings this awareness forward and lays the clockwork bare.

As for the future, Rath plans to keep making objects that question the division between human beings and the technology we create. He explains that each piece he makes begets a new one, and that he’s always working on multiple pieces at once, with no signs of slowing down. “If I never have a new idea, I still have a backlog of more pieces than I could ever make in my lifetime.”

Rath’s work regularly appears at the Hosfelt Gallery.

Alan Rath

Hosfelt Gallery

Facebook: alan.rath.artist

Instagram: alanrath

Twitter: alanrath

This article originally appeared in Issue 11.2 “Device”