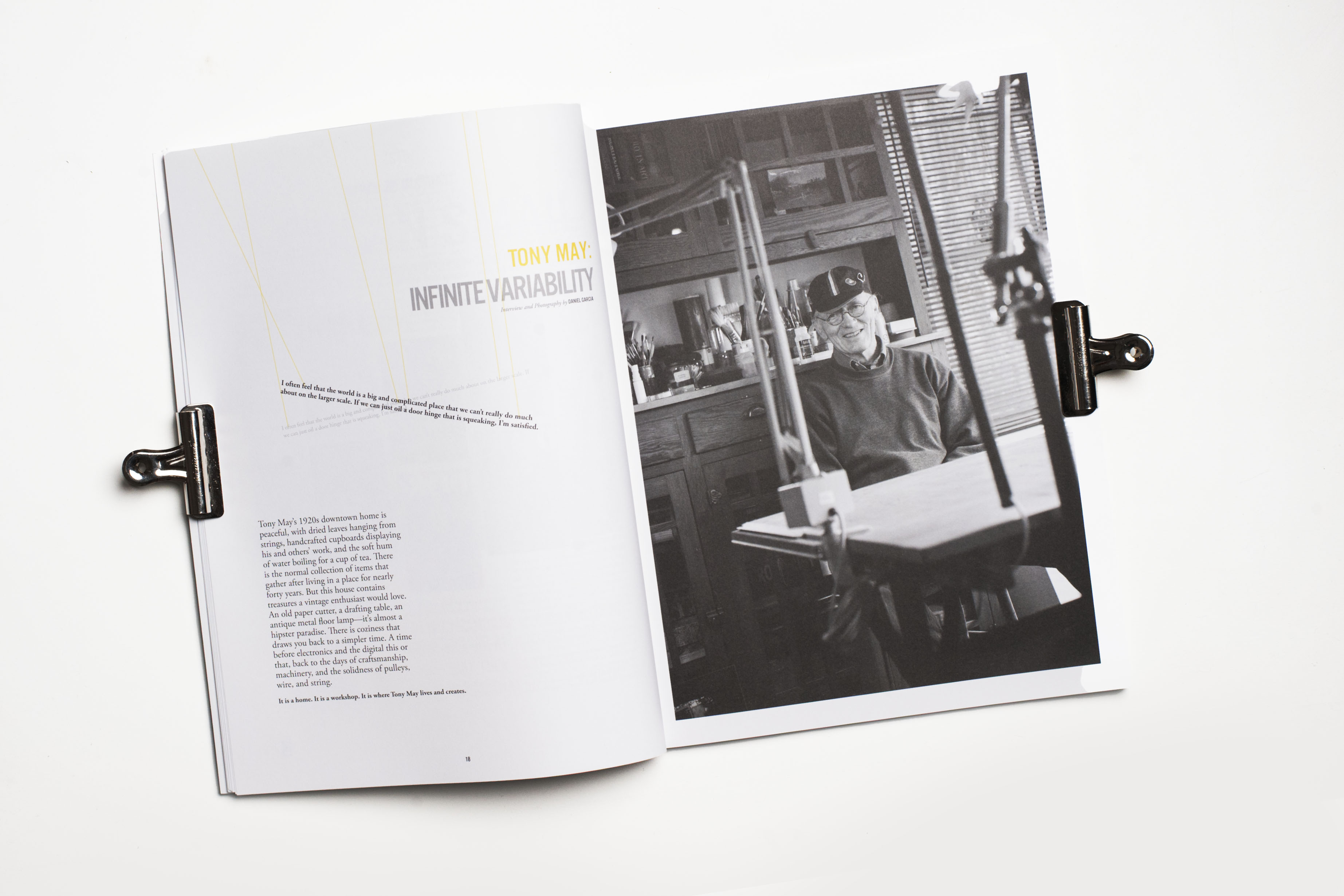

Tony May’s 1920s downtown home is peaceful, with dried leaves hanging from strings, handcrafted cupboards displaying his and others’ work, and the soft hum of water boiling for a cup of tea. There is the normal collection of items that gather after living in a place for nearly forty years. But this house contains treasures a vintage enthusiast would love. An old paper cutter, a drafting table, an antique metal floor lamp—it’s almost a hipster paradise. There is coziness that draws you back to a simpler time. A time before electronics and the digital this or that, back to the days of craftsmanship, machinery, and the solidness of pulleys, wire, and string.

It is a home. It is a workshop. It is where Tony May lives and creatives.

THE MATERIALS

You work with a variety of materials. Do you have a favorite?

Wood is my preferred medium, so I think of myself as more of a carpenter than anything else. I studied painting in college, and I had about three or four years of ceramics.

I left ceramics when the teacher finally gave me a B. I just had automatic A’s [up to then]. My professor finally gave me a B and said, “You’re not really into this, are you?” That’s when I started making those sculpture‑like things that were made out of the materials used in stretching canvas. I started doing those because I was getting so tired of making these really big, heavy, ceramic pieces that I couldn’t get rid of. [laughs]

So was it necessity, or were you looking for a new medium?

A little of both. I was lacking inspiration, trying to come up with interesting new forms in ceramics. I was struggling with making abstract things that had some scale to them, but I wasn’t yet skilled at making really big things. Plus, the kiln facilities were not huge, so I made a few pieces that were supposed to be large, but they were made of individual components and needed to be assembled after firing. You end up gluing pieces together with epoxies and making this crazy, monstrous thing.

When you’re moving from apartment to apartment, you’re lugging all these things around. The joke was, how many different stairways did I end up jettisoning ceramic pieces down in my career of moving two or three times in college?

That’s how the desire to make things that were more portable emerged. Then, it seemed like I was moving every year. Yet since 1973, I have stayed put in this house.

THE WORK

Your work has a nostalgic aspect to it. Where does that come from?

I’m enamored of 19th century technology. I always felt that my own skill level advanced pretty much up to then; it reached a plateau and never quite advanced beyond that.

Minimal art became very popular when I was in school. There were a lot of influences coming from that sort of thing, but I was focusing on sculpture. I like to think I was making something that would be like a John Chamberlain, because that’s what sculpture was by a certain definition at one time. But mine would be light and portable and variable. It wouldn’t be just one shape of abstract. It would be like this piece of cloth, but you could push it into all these different shapes. And then theoretically, you could get all kinds of emotive responses from it.

I was trying to make devices that would allow for this infinite variability, which, of course, they never achieved. But they were headed in that direction. It’s interesting, because now so much of what is being done in the virtual world and with computers is [about] not being satisfied with one image, but only with the kinetic, constantly varied image.

At a certain point with any of those kinetic pieces, as soon as you have that feeling of, “I think this is where we came in,” they’re no longer of interest—they’ve exhausted their possibilities of being interesting because of their variation. You’re inevitably returned back to the need to just produce a singular, static image that has that potential for expansion mentally, even though it’s not physically changing. I still think there’s room in the world for that kind of art. It doesn’t all have to be moving and blinking.

“I often feel that the world is a big and complicated place that we can’t really do much about on the larger scale. If we can just oil a door hinge that is squeaking, I’m satisfied.”

I was very influenced by performance art when I was in school. Steve French had this class in Madison that was focused on installation and performance. We did a bunch of performances that involved manipulating the audience. You know, taking the audience and almost abusing them. [laughs] Locking them up or something. Putting them in a position where they were ordered to do something—“OK, now you guys are going to do this.”

Then…making these structures, where instead of me deciding what the expressive object would look like, I would have a device that would allow the audience to make their own.

I sort of hate that whole thing. [laughs] I hate it when I go to some gallery and they say, “Hey, here’s a bunch of cool things. Why don’t you guys start making your own art with these?”

Bullshit! [laughs] I’m tired of that. I’m back to where I want the artist to actually make the art.

How do you think your work was affected by being a professor?

Well, it was reduced in quantity, because I didn’t have enough time to do it. On the other hand, I seem to have had just the perfect amount of time. I had all of the time that I couldn’t be doing it to be thinking about doing it. Some jobs get in the way of your production, but they help in a way, by forcing you to filter out the stuff that you probably never needed to do. The stuff that you really want to do rises to the top of your list.

In my personal work, I started fixing things in this house. I developed what seems to be a house fixation…or a house-fixing fixation. [laughs] I got so involved in fixing it up, and then doing odd things to it, then documenting those with paintings. It felt like this was a bonanza—I can do these obsessive-compulsive activities and then I can document them with obsessive-compulsive paintings!

A lot of my own art-making tendencies were directed into working collectively with students. I did a stint where I was doing temporary installation things with them. We made so many. Those vanished rather quickly after we finished them.

When I was doing group stuff, we worked democratically. I did have some rules. They were not allowed to do something I was convinced was going to get me in jail, for one thing. Or be seen as a negative contribution to the community. I think a lot of contemporary art does take that approach. Like, “Well, the world is really screwed up, so let’s screw it up some more to dramatize how screwed up it is.” I never thought that worked.

I suppose I realized that when I began to feel more secure in my profession, and to feel that being an art teacher wasn’t a total drag on society. [laughs] That there actually was some social benefit in working with students, and trying to get students to realize that they could accomplish quite a bit with very little means, just by employing their brains and their technical skills.

I often feel that the world is a big and complicated place that we can’t really do much about on the larger scale. If we can just oil a door hinge that is squeaking, I’m satisfied. A tiny little thing that you have mastered and you have under control. That seems to be somewhat satisfying, at least for a time.

I don’t think I ever thought that my work was going to change the world. I became aware of the fact that I could have some influence of a positive nature in my immediate community. By paying more attention to see if I can’t, as an artist, be a way of making a community better.

THE FUTURE

Is there something that you always want to do with your work, and you feel like you never are able to do it, and that keeps you going to the next project?

I have in my head a lot of projects I’m pretty sure I will never finish in my lifetime. I don’t know if I need to, but they’re there as goals. I will never run out of things that I want to do, which I feel very fortunate about. I guess my biggest fear is that I will run out of the energy I need to do them.

I spent years having forgotten I was raised on a farm in Wisconsin; that somehow it was all behind me, and it was no longer part of who I was. It’s like I’d outgrown it, I’d evolved. When I was in college, I thought I had definitely evolved, and I was now part of the cutting edge of the avant garde. And my parents were these local yokels that were completely unconnected to art in any way, and very unsophisticated.

In the last decade or so, I feel more than ever like this Midwestern farmer. It’s ironic, because I wanted nothing more than to get away from that place when I was a kid. I find that so much of that upbringing is still deeply ingrained in there; that self‑sufficiency, making do, and not having extravagant amounts of anything. I’ve come full circle.

FEATURED in Issue 5.1“Sight and Sound” – SOLD OUT